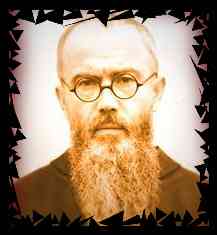

Some of my own knowledge of the figurine itself is foggy, as I no longer remember why his hand is missing. I do know that I purchased the figurine at a nunnery in Ohio many years ago.

The figurine is of one of my great heroes, a Catholic saint and priest. I almost always get the same reaction from my students. Typically, they pick him up and say something like "Oh, I like your monk action figure, Dr. Birzer." Usually, a slight but sympathetic laugh or giggle accompanies the question as they continue to examine the figure.

"Oh, do you know who that is?" I ask. The usual guess is: "St. Benedict"? A legitimate guess, especially given that we teach the rule of St. Benedict to all of our freshmen and that I have such a fondness for Miller's Canticle for Leibowitz.

No, I explain, this man died on August 14, 1941, in cell block 13, the worst of all punishments handed out by the National Socialists in Auschwitz prior to the employment of the ovens and gas chambers.

Kolbe, a Roman Catholic priest, had been taken prisoner by the Nazis, as had been vast number of his fellow men, Poles, Jews, Catholics, and Lutherans. The Nazis seemed to avoid discrimination when it came to state sanctioned murder.

On the last day of July, 1941, a prisoner had attempted to escape the terror camp. As punishment, the commandant called out 10 random names--the names of those to be executed in retribution for the one man trying to escape. One of the names called had belonged (or, rather, had been forced upon) a husband and father. As the man pleaded his case, Father Kolbe came forward and offered his life for the one pleading. The commandant, probably rather shocked, agreed, and Kolbe, with nine others, stripped naked, entered the 3-foot high concrete bunker. Deprived of food, water, light, and toilets, the men survived--unbelievably--for two weeks. Madness and cannibalism had never overcame them, as the Nazis had hoped. Instead, through Kolbe's witness as priest and preacher and as an incarnate soul made in the Image of Christ, grace pervaded the room. When the commandant had the room searched two weeks later, only to find the men and Father Kolbe alive, he furiously ordered them all to be injected with carbolic acid.

The man who removed Kolbe's body offered a wondrous testimony under oath. Kolbe, he said, had been in a state of definite ecstasy, his eyes focused on something far beyond the bunker, his arm outstretched, ready to accept the death of the chemicals to be injected in him.

At this point in the story, the student almost always puts down the figure of St. Maximilian Kolbe, a little surprised, a little overwhelmed, a little impressed, and with a bit of reverence.

No mere action figure sits on my desk.

There sits a representation of the saint of the twentieth century, patron of the 205 million men, women, and children murdered by their governments because they were each and every one of them an unrepeatable center for dignity and freedom, made for beauty and eternity, not for the whim of governor, bureaucrat, commandant, or ideologue.

The figurine is of one of my great heroes, a Catholic saint and priest. I almost always get the same reaction from my students. Typically, they pick him up and say something like "Oh, I like your monk action figure, Dr. Birzer." Usually, a slight but sympathetic laugh or giggle accompanies the question as they continue to examine the figure.

"Oh, do you know who that is?" I ask. The usual guess is: "St. Benedict"? A legitimate guess, especially given that we teach the rule of St. Benedict to all of our freshmen and that I have such a fondness for Miller's Canticle for Leibowitz.

No, I explain, this man died on August 14, 1941, in cell block 13, the worst of all punishments handed out by the National Socialists in Auschwitz prior to the employment of the ovens and gas chambers.

Kolbe, a Roman Catholic priest, had been taken prisoner by the Nazis, as had been vast number of his fellow men, Poles, Jews, Catholics, and Lutherans. The Nazis seemed to avoid discrimination when it came to state sanctioned murder.

On the last day of July, 1941, a prisoner had attempted to escape the terror camp. As punishment, the commandant called out 10 random names--the names of those to be executed in retribution for the one man trying to escape. One of the names called had belonged (or, rather, had been forced upon) a husband and father. As the man pleaded his case, Father Kolbe came forward and offered his life for the one pleading. The commandant, probably rather shocked, agreed, and Kolbe, with nine others, stripped naked, entered the 3-foot high concrete bunker. Deprived of food, water, light, and toilets, the men survived--unbelievably--for two weeks. Madness and cannibalism had never overcame them, as the Nazis had hoped. Instead, through Kolbe's witness as priest and preacher and as an incarnate soul made in the Image of Christ, grace pervaded the room. When the commandant had the room searched two weeks later, only to find the men and Father Kolbe alive, he furiously ordered them all to be injected with carbolic acid.

The man who removed Kolbe's body offered a wondrous testimony under oath. Kolbe, he said, had been in a state of definite ecstasy, his eyes focused on something far beyond the bunker, his arm outstretched, ready to accept the death of the chemicals to be injected in him.

At this point in the story, the student almost always puts down the figure of St. Maximilian Kolbe, a little surprised, a little overwhelmed, a little impressed, and with a bit of reverence.

No mere action figure sits on my desk.

There sits a representation of the saint of the twentieth century, patron of the 205 million men, women, and children murdered by their governments because they were each and every one of them an unrepeatable center for dignity and freedom, made for beauty and eternity, not for the whim of governor, bureaucrat, commandant, or ideologue.

[I published a version of this at Imaginative Conservative, a year ago today. Thanks to Winston Elliott for permission to repost.]

No comments:

Post a Comment